I don't know

The being and doing best cultivated through not knowing

How did the universe originate?

Are quantum fields conscious?

What does it mean to be human?

What does it mean to be human in the age of AI?

Where is our current political situation taking us?

Where should we focus our attention in an age of technofeudalism1?

Everyone likely has different answers to these questions. Is any of us unequivocally right?

Earlier this week I hosted an online class with students I work with as part of the MIT xPRO Post Graduate Certificate in Technology Leadership and Innovation course.

One student asked me: How do we identify ‘unknown unknowns’ when making decisions, to mitigate unwanted outcomes?

Feeling as though I should have answers, I suggested a couple ideas. We can build argument diagrams to test assumptions and surface unstated premises, or assemble a design structure matrix to gain a systems’ understanding of the sensitivity and connectivity of components within a product, process, or organization to predict emergency emergence. There are many tools or frameworks we could employ—sure.

But, as I’ve reflected since our class, there are sometimes questions we don’t and can’t know the answer to. We might research and compile data and run predictive models. Yet the more we learn, the more new questions form.

If we lust after enlightenment, after the Answer, we might be practicing a wrong attitude. The process of questioning and building our capacity to be with uncertainty might prove at least as valuable as any answers we discover along the way.

I’ve noticed at least two issues emerge when groups are facing uncertainty. One, how the person with the most power in the room can become impatient and force their idea. Two, groups remain endlessly mired in conversation, resistant to prototyping an idea because they don’t believe they know everything they need to know before getting started.

With regard to impatience leading to premature convergence, I liken it to an experience that can be had during breathwork. Yoga practitioner, Dylan Werner, says when we hold our breath for an extended time, we are tempted to break our posture early and inhale because we feel we do not have enough oxygen. When, in truth, we have plenty of oxygen2. What we are experiencing while holding our breath is a buildup of CO2 in our bloodstream. If we are seeking to lengthen our breath holds, we are really creating more CO2 tolerance.

Experiencing uncertainty might similarly feel as if we’re holding our breath and CO2 is accumulating in our bloodstream. Physically, whenever we do not know, our nervous system does tend to produce stress hormones until our brain detects predictability3. I wonder, then: How much capacity can we create to tolerate uncertainty? What if we waited longer than we wanted for answers, to see what might really want to happen?

Lately, as part of my morning rituals, I’ve been speaking aloud various ‘I AM’ statements to frame myself to live more abundantly while not knowing. One of them is:

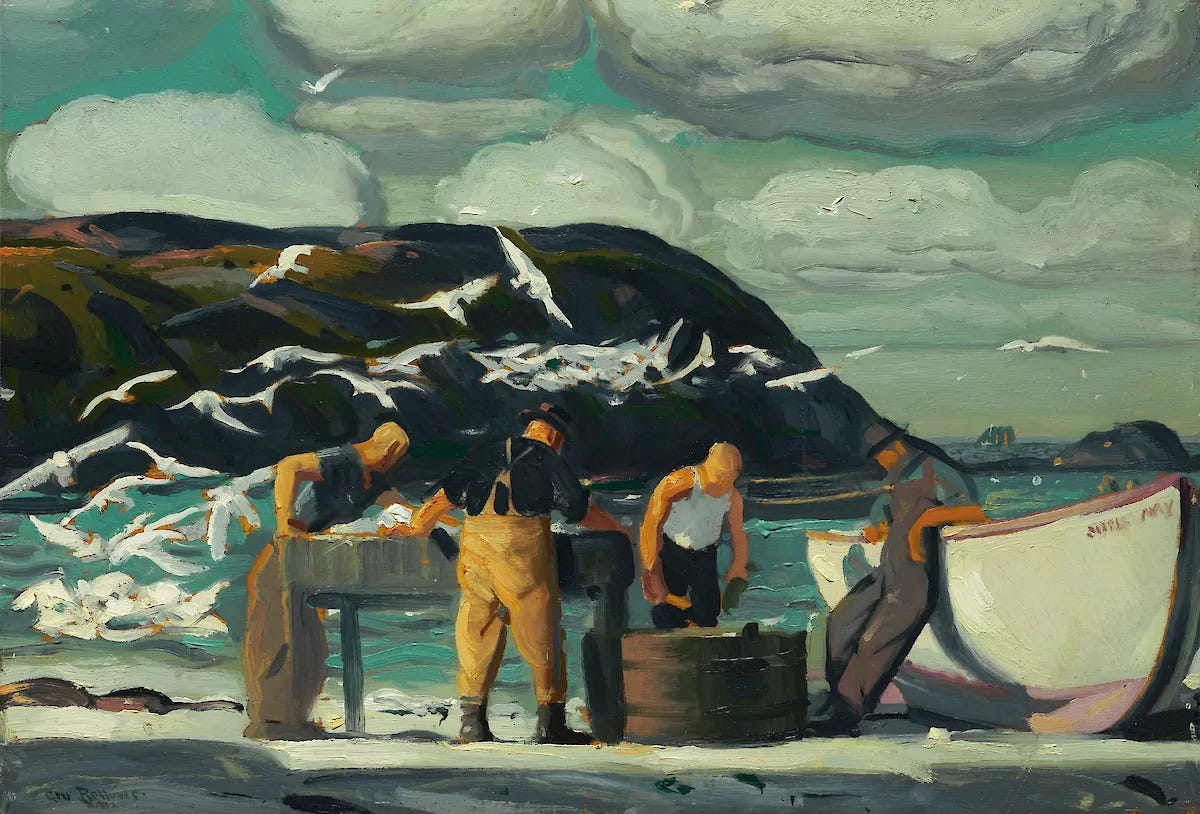

I am being. I am like a fisherman. Daily, I cast my line into the universe. I tune my antennae to the energetic material around and within me. I notice and observe, and am waiting longer than I want, to see what wants to come back.

Conversely, and to deal with the issue of resistance to trying out an idea, I have an I AM statement that forms a paradox with the previous one.

I am doing. I am like an artist. I prototype and experiment with the raw, colorful, energetic materials of the universe. I am designing in short stages. Living from nudge to nudge, I am bringing all of myself to make the finest work I can.

Whenever teams get stuck in muddy deliberation, I like to remind them, “You can’t know everything before you start.” If we hold an idea lightly enough, we can always create a low-resolution prototype, test it, make changes, or explore a different idea if the learnings coming back are coalescing in a more invigorating direction.

If we commit to being and doing while acknowledging we really “don’t know,” we train our muscles to embrace ambiguity. We gradually come alive, and so much else becomes possible.

Johnnie and I have updated our website to include ‘design coaching’ and our ‘annual group workshop’. You can take a closer look at our new offerings here. If you wish to becoming a ‘founding practitioner’ of unhurried design, you can select that option in your subscription to our Substack. You’ll be eligible to receive design coaching each year until you decide you don’t want it.

Yanis Varoufakis argues Apple, Meta, and Amazon have changed the economy so much that it now resembles Europe's medieval feudal system, and renames late-stage capitalism ‘technofeudalism’ in his book, Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism.

Don’t take this as a cue to try holding your breath for five minutes. You won’t survive. Unless you’re a freediver or Bajau Sea Nomad.

Elizabeth Menzel and Casey Hall, the two humans behind the “Slow the F Down Show,” a podcast, shared this with me during a conversation we had in 2021 as part of my inquiry into how hurry affects people and systems.

Really enjoyed the positive statement for creativity. So often people like to hide in the tower of "I am not creative". When we are literally creative beings and denying that part of ourselves is denying our "humanness". Well said👏